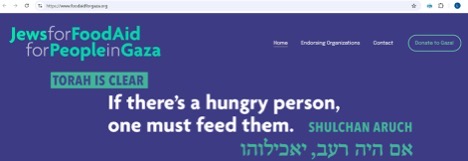

This week, someone forwarded me a screenshot from a website called Jews for Food Aid for People in Gaza. Big letters. Bold colors. A quote from the Shulchan Aruch—Jewish law:

“If there’s a hungry person, one must feed them.”

אם היה רעב יאכילוהו

And splashed across the top:

“The Torah is clear.”

I’ll be honest: I am conflicted

Because the Torah may be many things—ancient, holy, enduring—but rarely is it simple.

Especially not today.

Not when our hearts are still broken from October 7.

Not when over 58 hostages remain in Gaza.

Not when humanitarian aid often lands in the hands of Hamas.

Not when we’re trying to hold onto both compassion and truth—and feel like we’re failing at both.

So let’s ask the hard question out loud:

Are we obligated to feed the hungry even when they might want us dead?

Or, perhaps more pointedly: Are we permitted to withhold food if it might save lives?

What does Jewish law actually say?

Let’s begin where that website does—Yoreh De’ah 251:1, the Shulchan Aruch:

“One is obligated to feed the hungry.” Period.

This isn’t a modern value. It comes straight from Torah:

Deuteronomy 15:7–8 teaches:

“If there is a poor person among you… do not harden your heart… but surely open your hand to them.”

And notice—these texts don’t say:

Only if they’re Jewish.

Only if they’re innocent.

Only if they vote like you or mourn like you.

They say: if someone is hungry, you feed them.

The Talmud widens the circle. In Gittin 61a, it says:

“We support the poor of the non-Jews along with the poor of Israel—for the sake of peace.”

Maimonides codifies it in Hilchot Melachim 10:12:

“We are commanded to visit their sick, bury their dead, and support their poor alongside our own.”

This isn’t about optics. It’s a mitzvah. It’s Torah.

And yet… those sources weren’t written in the shadow of rockets.

They weren’t written after terrorists murdered entire families, kidnapped children, and livestreamed the horror.

We are not living in normal times.

So what happens when the person you’re feeding—or the regime they’re part of—has declared its intent to destroy you? What happens when food becomes a weapon?

This is where Jewish ethics becomes complex.

Another rabbinic principle enters the conversation:

“If someone comes to kill you, rise up and kill them first.” (Sanhedrin 72a)

Maimonides, in Hilchot Rotzeach, writes: Pikuach nefesh—preserving life—comes first. Always.

If feeding someone endangers Jewish lives, the halakhic obligation shifts.

Defending life takes precedence over feeding the hungry.

But that’s not the end of the story. It’s the beginning of a deeper one.

Because Jewish law doesn’t just ask what you do. It asks why you do it.

Are you withholding food because of real danger?

Or because you’ve stopped seeing the other side as human?

The Tosefta (Gittin 3:18) says:

“In a time of famine, we feed even the idolaters along with the Jews—for the sake of peace.”

This wasn’t about neighbors. These were Roman occupiers. Enemies.

And still, the rabbis said: feed them.

Why? Because even in conflict, you don’t lose your soul.

Even in war, you stay a mensch.

That’s why the Torah says:

“When you besiege a city in war, do not destroy its fruit trees.” (Deut. 20:19)

Even war has moral limits.

And here’s the truth:

In Gaza today, we don’t always know who the innocent are.

We don’t know if the food will reach them—or be hijacked by Hamas.

We don’t know if it will bring healing—or help dig the next tunnel.

And still—Judaism demands that we keep asking the question.

Because the danger is not just that we feed the wrong person.

It’s that we stop caring at all.

And once we stop asking, once we stop wrestling—we abandon our Jewish roots.

To those who call for sending food to Gaza, I say: I admire your compassion.

But compassion must also be clear-eyed.

You must ask: Will this aid truly reach the innocent? Or will it enable terror?

Empathy is not naiveté. It must come with moral seriousness.

And to those who say, “Let them starve—they cheered while we wept,”

I say with equal urgency:

That voice is not Jewish either.

We are commanded to defend ourselves.

We are never commanded to be cruel.

Our tradition warns against the chasid shoteh—the foolish pious person.

The one who means well but causes harm.

But it also warns against Pharaoh—whose heart became hard.

So what are we left with?

Feeding the hungry.

Protecting the innocent.

Balancing competing obligations—that’s the hardest mitzvah of all.

Because this isn’t a zero-sum game.

It’s a razor’s edge walk of moral courage.

And so we return to that verse:

“If there’s a hungry person, one must feed them.”

Is it always that simple? No.

Is it still our responsibility to wrestle with? Always.

Because Torah doesn’t live in slogans. It lives in struggle.

And if our hearts stay even a little open—

Even while grieving.

Even while afraid—

Then we’re still walking the path of Torah.

Shabbat Shalom.

Leave a Reply